The spirit and structure of German fascism

by John MacBeath Watkins

"Fascism" is a word that gets thrown around a lot, but it has achieved such a mythic status that it's easy to forget what a popular movement it was. We tend to think of it like passenger pigeons, a thing that once turned the sky black, but now is gone.

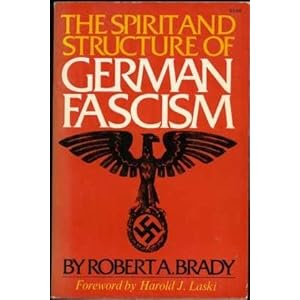

I've run across a 1937 book, The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism, written by American economist Robert A. Brady, who was enamored of Thorstein Veblen's approach to economics. Because he was writing before WW II, Brady was able to describe fascism as it was on the rise, without dismissing it as an aberration or simply an evil force like the ethereal epidemic forces blamed for disease before the discovery of germs.

The Great Depression led to unrest, gaining adherents for fringe parties on the left and right. In Germany, as in France, both the Communist Party and the Fascists gained strength. They offered contrasting visions of society; the Communists advocated a classless society where all men were equal, while the Fascists saw a rigid caste system as natural. The Social Darwinist strain in German politics -- sometimes called neo-Darwinism, and not to be confused with more recent uses of that term -- was there in World War I, as noted here.

The fascists believed so strongly in the heritability of merit that they insisted that sons of industrialists should be industrialists, the sons of laborers should be laborers, and so on. Germany had made the last forms of serfdom illegal less than 100 years before WW II, so the notion that people were born to their station was a familiar one in German culture. "Class war," therefore, was a crime against nature, not merely wrong, but repellent Keep that in mind next time you hear someone accuse people of "class war."

The Fascists did not consider science objective. Each nation had a science natural to them, they maintained, and any science that claimed to be universal was "Jewish" and false. The "science" of racial hygiene was far more acceptable.

They offered a suffering people a scapegoat to blame. The first German pogrom was in the 11th century and they continued for centuries, so this had a familiar feel as well.

The Führerprinzip, or leader principle, dictated that some are born to lead, some are born to follow, and the Führer's word superseded any written law. This is why people of the generation that fought World War II were struck by Richard Nixon's explanation that "when the president does it, that means it's not illegal." It smacked of the Führerprinzip.

Because the leader was wise, and the people should obey, a leader could use whatever means necessary to persuade people to do what needed to be done. This willingness to mislead in order to lead is similar to Lenin's theory that the intellectual vanguard could say whatever they needed to in order to get people to do what was needed.

"Totalitarian" is a term invented by Italian Fascists, and was aspirational rather than condemnatory. Mussolini boasted that Fascism politicized everything spiritual and human: "Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state."

Professional norms for government prosecutors, for example, would be replaced by the political expediency of the Fascist Party. It's the ultimate in big-government conservatism; as Goebbels noted, people could think and say whatever they liked as long as they didn't mind going to a concentration camp. Brady's book, published in 1937, quoted that remark, so it wasn't just a wartime expediency, it was a peacetime policy as well. I know a number of intellectuals died in concentration camps for what they said against fascism, but I've never seen a figure for how many.

We should keep two things in mind about fascism. One is that not only are officially fascist parties banned in Italy and Germany, politicians are aware that they have a branding problem, so any politician who adopts the aims or methods of the fascists will not only avoid the label, they will object strenuously to its application to them.

The second is somewhat countervailing to the first. I call it the "shave the whales" problem, in honor of Scott Adams' cartoon illustrating the problem. The reasoning goes like this: Whales are mammals. Mammals are hairy. Shave the whales.

Similarly, we might point out that Hitler was a vegetarian. Hitler was a Nazi. Not all vegetarians, however, are Nazi.

When people adopt the aims and methods once associated with fascism, we should object to them for the harm they do, not who was associated with them. The value of a book like Brady's is that it helps us know where such ideas lead.

"Fascism" is a word that gets thrown around a lot, but it has achieved such a mythic status that it's easy to forget what a popular movement it was. We tend to think of it like passenger pigeons, a thing that once turned the sky black, but now is gone.

I've run across a 1937 book, The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism, written by American economist Robert A. Brady, who was enamored of Thorstein Veblen's approach to economics. Because he was writing before WW II, Brady was able to describe fascism as it was on the rise, without dismissing it as an aberration or simply an evil force like the ethereal epidemic forces blamed for disease before the discovery of germs.

The Great Depression led to unrest, gaining adherents for fringe parties on the left and right. In Germany, as in France, both the Communist Party and the Fascists gained strength. They offered contrasting visions of society; the Communists advocated a classless society where all men were equal, while the Fascists saw a rigid caste system as natural. The Social Darwinist strain in German politics -- sometimes called neo-Darwinism, and not to be confused with more recent uses of that term -- was there in World War I, as noted here.

The fascists believed so strongly in the heritability of merit that they insisted that sons of industrialists should be industrialists, the sons of laborers should be laborers, and so on. Germany had made the last forms of serfdom illegal less than 100 years before WW II, so the notion that people were born to their station was a familiar one in German culture. "Class war," therefore, was a crime against nature, not merely wrong, but repellent Keep that in mind next time you hear someone accuse people of "class war."

The Fascists did not consider science objective. Each nation had a science natural to them, they maintained, and any science that claimed to be universal was "Jewish" and false. The "science" of racial hygiene was far more acceptable.

They offered a suffering people a scapegoat to blame. The first German pogrom was in the 11th century and they continued for centuries, so this had a familiar feel as well.

The Führerprinzip, or leader principle, dictated that some are born to lead, some are born to follow, and the Führer's word superseded any written law. This is why people of the generation that fought World War II were struck by Richard Nixon's explanation that "when the president does it, that means it's not illegal." It smacked of the Führerprinzip.

Because the leader was wise, and the people should obey, a leader could use whatever means necessary to persuade people to do what needed to be done. This willingness to mislead in order to lead is similar to Lenin's theory that the intellectual vanguard could say whatever they needed to in order to get people to do what was needed.

"Totalitarian" is a term invented by Italian Fascists, and was aspirational rather than condemnatory. Mussolini boasted that Fascism politicized everything spiritual and human: "Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state."

Professional norms for government prosecutors, for example, would be replaced by the political expediency of the Fascist Party. It's the ultimate in big-government conservatism; as Goebbels noted, people could think and say whatever they liked as long as they didn't mind going to a concentration camp. Brady's book, published in 1937, quoted that remark, so it wasn't just a wartime expediency, it was a peacetime policy as well. I know a number of intellectuals died in concentration camps for what they said against fascism, but I've never seen a figure for how many.

We should keep two things in mind about fascism. One is that not only are officially fascist parties banned in Italy and Germany, politicians are aware that they have a branding problem, so any politician who adopts the aims or methods of the fascists will not only avoid the label, they will object strenuously to its application to them.

The second is somewhat countervailing to the first. I call it the "shave the whales" problem, in honor of Scott Adams' cartoon illustrating the problem. The reasoning goes like this: Whales are mammals. Mammals are hairy. Shave the whales.

Similarly, we might point out that Hitler was a vegetarian. Hitler was a Nazi. Not all vegetarians, however, are Nazi.

When people adopt the aims and methods once associated with fascism, we should object to them for the harm they do, not who was associated with them. The value of a book like Brady's is that it helps us know where such ideas lead.

Comments

Post a Comment