How austerity critics lie with statistics

by John MacBeath Watkins

There's a new meme going around in conservative circles. They look at European budgets and ask, "what austerity?"

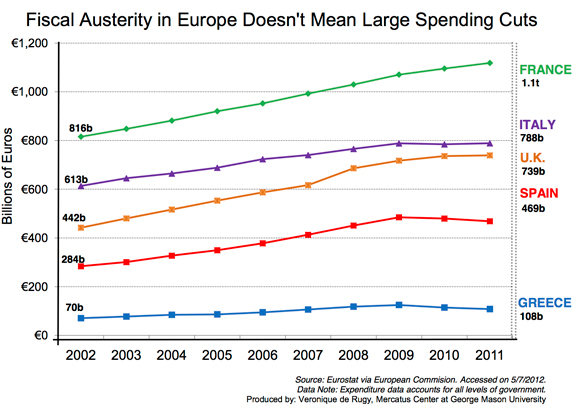

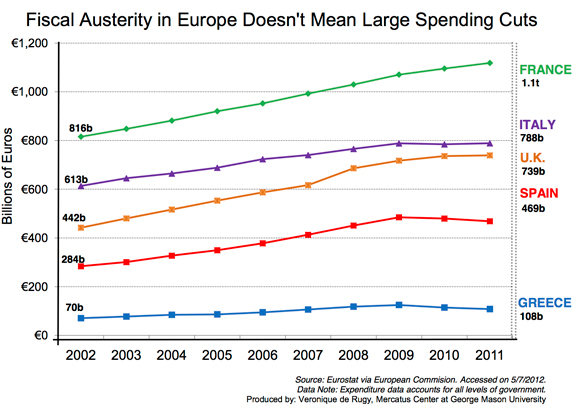

And illustrate their question with this chart or the numbers that went into it:

But when we put it in Euros and include 2011, it looks like this:

And, of course, Veronique de Rugy, who compiled this data, is right about one thing. It's not so much that the budgets have been reduced as that they've been reallocated. With an unemployment rate of almost 25%, social insurance costs must be skyrocketing in Spain, and the cost of interest on the debt is skyrocketing as well. Civil service salaries have been cut, spending on everything else has been cut, but Spain's borrowing costs are high and the reason for this is that their banks collapsed, and the government decided to bail them out. Now the taxpayers are paying back debts they did not incur, because the Spanish banks borrowed a lot of money they can't repay, much of it from German banks.

Where the source for these charts is wrong is when she says this:

But the Spanish debt as a percent of GDP was actually quite small before the banking crisis. Two things have pushed it up: bailing out the banks, and the decline in GDP, which in Spain is at Depression levels (from here.) After all, every fraction has a denominator as well as a numerator.

One-size-fits-all approaches to the crisis put Spain in the same category as Greece, where the government was profligate and dishonest. As Paul De Grauwe's chart shows, Spain was actually reducing its debt as a percent of GDP until its banks failed.

How would a budget look in a European country where there was no bank bailout and social insurance kicked in as the economy slowed without a major effort to reduce debt? And what would borrowing look like if they could borrow more? Probably like Germany's spending and borrowing looked:

In 2009, right where the German budget shows the uptick we would expect from higher social insurance costs, the German budget shows an uptick where the Spanish and Greek budgets take a downturn. And remember, Spanish unemployment is much, much worse than German unemployment.

So, in countries like Spain, instead of borrowing like Germany, they are raising taxes, and instead of keeping civil servants' salaries the same, they are lowering them and spending the money on unemployment insurance and paying interest on debt, a substantial part of which was borrowed by local banks from German and French banks and loaned to citizens to buy houses they can no longer afford because they don't have jobs. And in Spain, even if you give back the house, you still owe the loan until you pay it back or die. Household deleveraging under these circumstances seems pretty much impossible.

How is that not austere?

Update:

And it turns out my favorite magazine, The Economist, agrees with me: http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2012/05/euro-crisis-0

And they show it with charts. Go to the link to view them, you really should read it.

There's a new meme going around in conservative circles. They look at European budgets and ask, "what austerity?"

And illustrate their question with this chart or the numbers that went into it:

But when we put it in Euros and include 2011, it looks like this:

And, of course, Veronique de Rugy, who compiled this data, is right about one thing. It's not so much that the budgets have been reduced as that they've been reallocated. With an unemployment rate of almost 25%, social insurance costs must be skyrocketing in Spain, and the cost of interest on the debt is skyrocketing as well. Civil service salaries have been cut, spending on everything else has been cut, but Spain's borrowing costs are high and the reason for this is that their banks collapsed, and the government decided to bail them out. Now the taxpayers are paying back debts they did not incur, because the Spanish banks borrowed a lot of money they can't repay, much of it from German banks.

Where the source for these charts is wrong is when she says this:

Following years of large spending expansion, Spain, the United Kingdom, France, and Greece—countries widely cited for adopting austerity measures—haven’t significantly reduced spending since “austerity” supposedly started in 2008.

But the Spanish debt as a percent of GDP was actually quite small before the banking crisis. Two things have pushed it up: bailing out the banks, and the decline in GDP, which in Spain is at Depression levels (from here.) After all, every fraction has a denominator as well as a numerator.

One-size-fits-all approaches to the crisis put Spain in the same category as Greece, where the government was profligate and dishonest. As Paul De Grauwe's chart shows, Spain was actually reducing its debt as a percent of GDP until its banks failed.

How would a budget look in a European country where there was no bank bailout and social insurance kicked in as the economy slowed without a major effort to reduce debt? And what would borrowing look like if they could borrow more? Probably like Germany's spending and borrowing looked:

In 2009, right where the German budget shows the uptick we would expect from higher social insurance costs, the German budget shows an uptick where the Spanish and Greek budgets take a downturn. And remember, Spanish unemployment is much, much worse than German unemployment.

So, in countries like Spain, instead of borrowing like Germany, they are raising taxes, and instead of keeping civil servants' salaries the same, they are lowering them and spending the money on unemployment insurance and paying interest on debt, a substantial part of which was borrowed by local banks from German and French banks and loaned to citizens to buy houses they can no longer afford because they don't have jobs. And in Spain, even if you give back the house, you still owe the loan until you pay it back or die. Household deleveraging under these circumstances seems pretty much impossible.

How is that not austere?

Update:

And it turns out my favorite magazine, The Economist, agrees with me: http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2012/05/euro-crisis-0

And they show it with charts. Go to the link to view them, you really should read it.

Comments

Post a Comment