The cage of addiction: Filling the emptiness with oblivion

by John MacBeath Watkins

The first time I met my cousin Mark, he tried to hit me with a truck.

It was a Tonka, so he wasn't driving it. He was about five, I was a little older

His family visited years later, when I was 13. He attacked me, we wrestled, and I demonstrated that being wiry and understanding leverage is better than being a bit bigger. He seemed to want to establish dominance rather than build a connection each time we met.

Mark went on to become a commercial fisherman who drank so heavily that his liver was a smoking ruin by the time he was in his 40s. My extended family has not been touched much by addiction, so Mark's difficulties are some of the little personal contact with addiction I have. Mark grew up in a loving family, and no others in that family have had this problem. But I wonder, in retrospect, if his aggression was part of a difficulty in connecting to people. That may have been the real problem.

A team of researchers at Simon Frasier University started exploring this problem in 1977. I was living in Seattle at the time, Mark was living in Alaska, and the research was happening in the Canadian space between us. The classic research on addiction had been done with an experiment involving rats in cages.

Rats were set up with a self-injection system and taught to use it to administer heroin to themselves. Placed in a cage with access to food, water, and heroin, most rats would administer heroin to the exclusion of eating and drinking until they died. This was the basis for the drug war, a version of addiction that said the cause of addiction is the drugs, so we can only avoid the problem of addiction by interdicting the drugs, or keeping drug addicts away from drugs.

Canadians James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954 even demonstrated that rats would do this to get electric stimulation of their brain's pleasure centers until death overtook them.

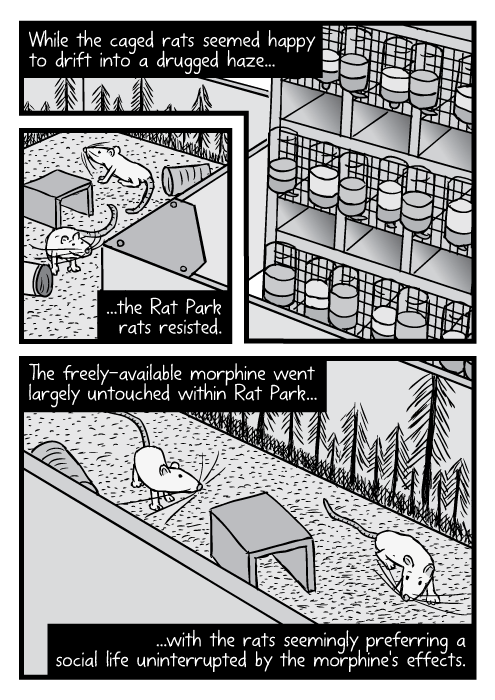

But in 1977 lead investigator Bruce Alexander at Simon Frasier wondered if he'd do the same in solitary confinement with only the heroin/cocaine/electrode-in-his-brain as solace. So the Simon Frasier team tried it a different way. First, they got the rats addicted by using the now familiar form of the experiment, placing them in standard mesh cages, unable to see or touch other rats, with a choice of plain water or water laced with morphine. After 57 days, the rats were well and truly hooked.

Then, they moved half of them to Rat Park, a 95-square-foot facility with things to play with, space to mate and raise litters, and a generally pleasant environment with the company of 16-20 other rats.

Almost all the rats shunned the morphine water and chose to live the sort of social life rats in nature live.

This echos the experience of troops returning from Viet Nam. Something like 20% of soldiers who served in Viet Nam used heroin. When they came home, about 95% of them never used it again. No special programs, all we did was take them out of a terrifying dystopia and put them in a supportive and normal environment, surrounded by family and friends.

Which makes me wonder. I have no difficulty connecting with Mark's parents or his sisters, but I never felt I could connect with him at all. We look at the wreckage of peoples' lives associated with addiction, and we assume that correlation means causation, that addiction has brought about the wreckage. But what if it simply has the same cause as the wreckage? Mark got married, had a lovely wife and children, who in the end left him. Was the problem that alcohol wrecked the marriage, or was it that the same demons that made Mark unable to sustain the marriage were what drove him to drink?

When people get into a 12-step program, one thing it does is give them a group of people to connect to. I wonder now, looking back at the tragedy of Mark's life, if that is not the most important part of the cure. Sometimes I think of a couple who were alcoholics, and of how little comfort they seemed to take in each other or in their children, seeking dominance rather than comfort in their relationships. They were living in Rat Park, but they had built themselves a cage, and filled the emptiness of the void with oblivion.

So, if we catch an addicts with their drugs, what do we do with them? We put them in a cage, a panopticon dystopia, separated from anyone they love.

Good luck with that.

We have a huge system built to enforce our erroneous assumptions about the nature of addiction. The system itself blights lives, and does not solve the problem. We need to find a better way.

The first time I met my cousin Mark, he tried to hit me with a truck.

It was a Tonka, so he wasn't driving it. He was about five, I was a little older

His family visited years later, when I was 13. He attacked me, we wrestled, and I demonstrated that being wiry and understanding leverage is better than being a bit bigger. He seemed to want to establish dominance rather than build a connection each time we met.

Mark went on to become a commercial fisherman who drank so heavily that his liver was a smoking ruin by the time he was in his 40s. My extended family has not been touched much by addiction, so Mark's difficulties are some of the little personal contact with addiction I have. Mark grew up in a loving family, and no others in that family have had this problem. But I wonder, in retrospect, if his aggression was part of a difficulty in connecting to people. That may have been the real problem.

A team of researchers at Simon Frasier University started exploring this problem in 1977. I was living in Seattle at the time, Mark was living in Alaska, and the research was happening in the Canadian space between us. The classic research on addiction had been done with an experiment involving rats in cages.

Rats were set up with a self-injection system and taught to use it to administer heroin to themselves. Placed in a cage with access to food, water, and heroin, most rats would administer heroin to the exclusion of eating and drinking until they died. This was the basis for the drug war, a version of addiction that said the cause of addiction is the drugs, so we can only avoid the problem of addiction by interdicting the drugs, or keeping drug addicts away from drugs.

Canadians James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954 even demonstrated that rats would do this to get electric stimulation of their brain's pleasure centers until death overtook them.

But in 1977 lead investigator Bruce Alexander at Simon Frasier wondered if he'd do the same in solitary confinement with only the heroin/cocaine/electrode-in-his-brain as solace. So the Simon Frasier team tried it a different way. First, they got the rats addicted by using the now familiar form of the experiment, placing them in standard mesh cages, unable to see or touch other rats, with a choice of plain water or water laced with morphine. After 57 days, the rats were well and truly hooked.

Then, they moved half of them to Rat Park, a 95-square-foot facility with things to play with, space to mate and raise litters, and a generally pleasant environment with the company of 16-20 other rats.

Almost all the rats shunned the morphine water and chose to live the sort of social life rats in nature live.

This echos the experience of troops returning from Viet Nam. Something like 20% of soldiers who served in Viet Nam used heroin. When they came home, about 95% of them never used it again. No special programs, all we did was take them out of a terrifying dystopia and put them in a supportive and normal environment, surrounded by family and friends.

Which makes me wonder. I have no difficulty connecting with Mark's parents or his sisters, but I never felt I could connect with him at all. We look at the wreckage of peoples' lives associated with addiction, and we assume that correlation means causation, that addiction has brought about the wreckage. But what if it simply has the same cause as the wreckage? Mark got married, had a lovely wife and children, who in the end left him. Was the problem that alcohol wrecked the marriage, or was it that the same demons that made Mark unable to sustain the marriage were what drove him to drink?

When people get into a 12-step program, one thing it does is give them a group of people to connect to. I wonder now, looking back at the tragedy of Mark's life, if that is not the most important part of the cure. Sometimes I think of a couple who were alcoholics, and of how little comfort they seemed to take in each other or in their children, seeking dominance rather than comfort in their relationships. They were living in Rat Park, but they had built themselves a cage, and filled the emptiness of the void with oblivion.

So, if we catch an addicts with their drugs, what do we do with them? We put them in a cage, a panopticon dystopia, separated from anyone they love.

Good luck with that.

We have a huge system built to enforce our erroneous assumptions about the nature of addiction. The system itself blights lives, and does not solve the problem. We need to find a better way.

Comments

Post a Comment