Which classic superheroes were gay? The ones with a secret identity?

by John MacBeath Watkins

I was the sort of nerdy kid who read a lot of science fiction and comic books. Specifically, I was a Marvel Comics kid.

I was also not particularly socially aware. Not being gay, homosexual characters didn't particularly register with me. I read The Last of the Wine and thought, huh, things were kind of different in ancient Greece, and went on to read The Bull from the Sea, which had a hero I found easier to identify with.

So when Stan Lee, author of so many great Marvel comic books, said in a 2002 interview that one of the characters in Nick Fury's Howling Commandos was gay, I wasn't at all surprised that I'd missed it. And the character was named Percival "Pinky" Pinkerton. A blatant clue, that.

But of course, Stan Lee wrote that character in the mid 1960s, when homosexuality was still The Love That Dare Not Speak its Name, so writers had to be a bit circumspect. Now that homosexuality has become The Love That Just Can't Stop Talking About Itself (or, more rudely, The Love That Will Not Shut Its Trap,) comic books need to keep up with the times. Green Lantern has come out of the closet. Marvel Comics, as usual the edgier franchise, is having one of its characters (Northstar, who I guess is Marvel's version of The Flash) marrying his long-time companion.

Pinky Pinkerton raises another issue, however. How many of these characters were gay all along, and we never guessed?

I'm thinking it's the ones that clearly spent a lot of time in the gym, wore colorful, tight-fitting outfits, and spent their time hanging out with similarly buff, colorfully-attired companions, and had to conceal this, the most satisfying part of their identity by pretending to be normal and ordinary.

Let's face it, people with extraordinary physical gifts don't typically make a secret of it. The ability to run faster or jump higher than other people, or to beat large opponents into a state of deep unconsciousness, are actually of minimal value in fighting crime. They can, however, bring you fame and fortune on the open market.

Bruce Wayne had to start out rich. Michael Jordan used his physical gifts to get rich. And he got to let everyone know who he was and how great he was.

It's pretty obvious why superheroes appeal to wimpy introverts like the 12-year-old version of me. We are the secret identity that no one would expect to learn was powerful and heroic, a facade we can easily maintain because we are not, in actual fact, powerful or heroic. Coming up with excuses for the powerful and heroic to pretend to be us, to be normal and ordinary, is more difficult.

Now, however, it occurs to me that our ordinariness and normality were our super power to those who were neither. The tragedy of the secret identity, for those who actually needed one, was that it represented a power they aspired to, the power of social acceptance.

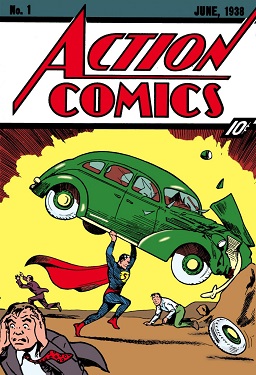

Some kids wanted to be Superman. Some just wanted to pass for Clark Kent.

I was the sort of nerdy kid who read a lot of science fiction and comic books. Specifically, I was a Marvel Comics kid.

I was also not particularly socially aware. Not being gay, homosexual characters didn't particularly register with me. I read The Last of the Wine and thought, huh, things were kind of different in ancient Greece, and went on to read The Bull from the Sea, which had a hero I found easier to identify with.

So when Stan Lee, author of so many great Marvel comic books, said in a 2002 interview that one of the characters in Nick Fury's Howling Commandos was gay, I wasn't at all surprised that I'd missed it. And the character was named Percival "Pinky" Pinkerton. A blatant clue, that.

But of course, Stan Lee wrote that character in the mid 1960s, when homosexuality was still The Love That Dare Not Speak its Name, so writers had to be a bit circumspect. Now that homosexuality has become The Love That Just Can't Stop Talking About Itself (or, more rudely, The Love That Will Not Shut Its Trap,) comic books need to keep up with the times. Green Lantern has come out of the closet. Marvel Comics, as usual the edgier franchise, is having one of its characters (Northstar, who I guess is Marvel's version of The Flash) marrying his long-time companion.

Pinky Pinkerton raises another issue, however. How many of these characters were gay all along, and we never guessed?

|

| Is there any hope for Lois Lane? |

Let's face it, people with extraordinary physical gifts don't typically make a secret of it. The ability to run faster or jump higher than other people, or to beat large opponents into a state of deep unconsciousness, are actually of minimal value in fighting crime. They can, however, bring you fame and fortune on the open market.

Bruce Wayne had to start out rich. Michael Jordan used his physical gifts to get rich. And he got to let everyone know who he was and how great he was.

It's pretty obvious why superheroes appeal to wimpy introverts like the 12-year-old version of me. We are the secret identity that no one would expect to learn was powerful and heroic, a facade we can easily maintain because we are not, in actual fact, powerful or heroic. Coming up with excuses for the powerful and heroic to pretend to be us, to be normal and ordinary, is more difficult.

Now, however, it occurs to me that our ordinariness and normality were our super power to those who were neither. The tragedy of the secret identity, for those who actually needed one, was that it represented a power they aspired to, the power of social acceptance.

Some kids wanted to be Superman. Some just wanted to pass for Clark Kent.

Comments

Post a Comment