Consensus, debt, risk: A legislature that "can’t be trusted to govern the country in a responsible manner"

by John MacBeath Watkins

Japan has a debt load of 225.8 percent of GDP, as reported by the CIA World Fact Book. Italy, at 118.1 percent, has a little over half the debt load Japan has, yet it must pay much higher interest rates to borrow, reflecting a higher risk of not repaying. (interestingly, there are different ways of totaling national debt. America looks pretty good in the CIA World Fact Book, not so good in the IMF numbers. Japan and Italy look about the same regardless of whose numbers you use.)

Why would Italy be less likely to repay its proportionately smaller debt?

Both Japan and Italy have terrible demographic profiles, having had a low birth rate for quite a few years and being unreceptive to immigrants as a solution to that problem. Both are doing poorly economically at the moment.

One big difference, of course, is that Italy does not control its own currency or central bank. but another is simply, the consensus for its government to act responsibly.

No matter who the Japanese elect, they seem to be responsible, if a bit slow-moving. The Italians, on the other hand, seem to chose their governments for their entertainment potential. Compared to the drab, ethics-bound Japanese politicians, Silvio Berlusconi has provided both comedy and drama. Outside of Italy, it's kind of hard to take his administration seriously, and the opposition has not shown enough strength to replace him.

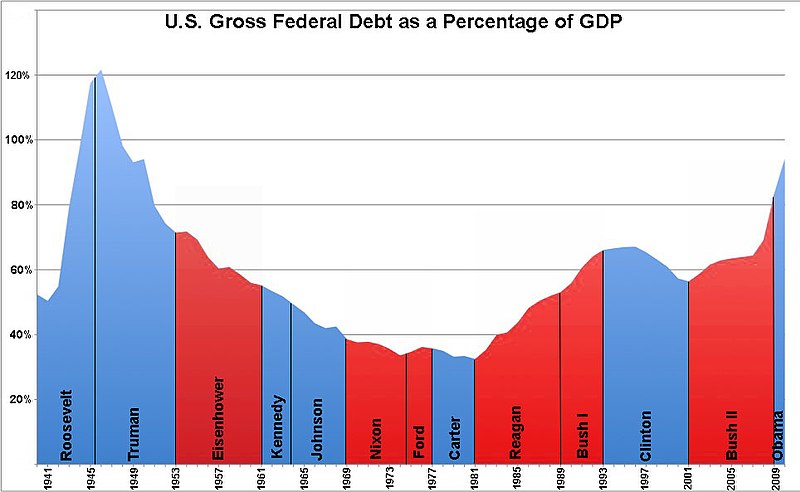

Certainly, politics are important to investors in sovereign debt. Take a look at this chart of American sovereign debt (from here. You can click on it to make it larger.)

Debt as a percentage of GDP fell during the post-WW II era in which the work of John Maynard Keynes underpinned a wide consensus among economists about how the economy works. That period encompassed four Democratic administrations and three Republican ones. Carter was the last president before the Keynesian consensus broke down.

Monetarists, the leading light of whom was Milton Friedman, felt they had a better way, and Republican politicians latched onto supply-side economics and in particular to the "Laffer Curve," which seemed to promise something for nothing, claiming lowering taxes would increase the amount of tax paid. We see the result in the Reagan administration and both Bush administrations.

(Laffer, by the way, did not claim to have invented the theory, attributing it to 14th century Muslim philosopher Ibn Khaldun. Laffer did, however, contribute to the theory by claiming it applied at American levels of taxation, and tax-cut enthusiasts seem to have decided that it applies to almost any level of taxation.)

Keynesian theory says that in economic booms, you should reduce the outstanding debt, and in bad times, government should be ready to put money into the economy to jump-start it. The breakdown in the Keynesian consensus has been accompanied by a breakdown in the consensus that we should pay down the debt in good economic times.

Of course, partisan politics plays a part in all this, as we discussed in this post. Republicans don't mind increasing the debt when a Republican is in the White House, as we discussed here. In fact, the Republican consensus in favor of George W. Bush's stimulus package in 2008 would appear to show that they do, in fact, believe government action can jump-start the economy, and the Republican consensus against the Obama stimulus might actually be because they thought it might work, and help him get re-elected. Such strategic thinking might also be why Republicans were eager to force President Bill Clinton to cut the deficit, and voted repeatedly for tax and spending legislation during the second Bush administration that sent the deficit skyrocketing.

I think the problem here is that the Keynesian consensus has not really been replaced by either a new consensus or by two competing consensus (consensi?) Many of those determining our public policy have abandoned any real model of how the economy works, and now simply look for justifications for policies they want anyway.

For example, when the economy was booming and the budget was in surplus as President George W. Bush entered office, his solution to this policy challenge was to lower taxes. When the economy was hemorrhaging jobs and the budget was hemorrhaging red ink, his solution was a tax giveaway. Opposite conditions demanded the same response in his view, because any problem the country faced was an opportunity to pursue his political agenda.

This was the response of a man for whom economic analysis had no meaning; only political agendas had meaning.

On the Democrats' side, there is what might be called a weak Keynesian consensus. President Barak Obama, for example, seems to seek a middle ground between his own followers and the Republicans, a ground which arguably does not exist.

In any society, you must have elites who are expert on various topics, and can be counted on for sage words when advice is needed. We lack a consensus about who those experts are on any number of topics, in part because of a deliberate policy of agnotology, in part because dividing the nation was a deliberate strategy pursued by one of our political parties since the 1960s, a process very well described by George Packer's May, 2008 article on the subject in the New Yorker, which I keep finding myself urging people to read.

Nixon's Southern strategy depended on harnessing the resentment of Southern whites. Pat Buchanan wrote a 1971 memo to Nixon that encapsulated that strategy (which had been successful in the 1968 campaign) as using the resentments of Southern and working-class whites to “cut the Democratic Party and country in half; my view is that we would have far the larger half.”

Consensus and trust in elites are things more easily destroyed than restored, and thus far the electoral process is providing few incentives for our politicians to work this out.

Consider this, from Felix Salmon's financial blog:

A legislature that "can’t be trusted to govern the country in a responsible manner" sounds more like the Italian government than the Japanese one. And that is an economic problem only because it is a political one.

Japan has a debt load of 225.8 percent of GDP, as reported by the CIA World Fact Book. Italy, at 118.1 percent, has a little over half the debt load Japan has, yet it must pay much higher interest rates to borrow, reflecting a higher risk of not repaying. (interestingly, there are different ways of totaling national debt. America looks pretty good in the CIA World Fact Book, not so good in the IMF numbers. Japan and Italy look about the same regardless of whose numbers you use.)

Why would Italy be less likely to repay its proportionately smaller debt?

Both Japan and Italy have terrible demographic profiles, having had a low birth rate for quite a few years and being unreceptive to immigrants as a solution to that problem. Both are doing poorly economically at the moment.

One big difference, of course, is that Italy does not control its own currency or central bank. but another is simply, the consensus for its government to act responsibly.

No matter who the Japanese elect, they seem to be responsible, if a bit slow-moving. The Italians, on the other hand, seem to chose their governments for their entertainment potential. Compared to the drab, ethics-bound Japanese politicians, Silvio Berlusconi has provided both comedy and drama. Outside of Italy, it's kind of hard to take his administration seriously, and the opposition has not shown enough strength to replace him.

Certainly, politics are important to investors in sovereign debt. Take a look at this chart of American sovereign debt (from here. You can click on it to make it larger.)

Debt as a percentage of GDP fell during the post-WW II era in which the work of John Maynard Keynes underpinned a wide consensus among economists about how the economy works. That period encompassed four Democratic administrations and three Republican ones. Carter was the last president before the Keynesian consensus broke down.

Monetarists, the leading light of whom was Milton Friedman, felt they had a better way, and Republican politicians latched onto supply-side economics and in particular to the "Laffer Curve," which seemed to promise something for nothing, claiming lowering taxes would increase the amount of tax paid. We see the result in the Reagan administration and both Bush administrations.

(Laffer, by the way, did not claim to have invented the theory, attributing it to 14th century Muslim philosopher Ibn Khaldun. Laffer did, however, contribute to the theory by claiming it applied at American levels of taxation, and tax-cut enthusiasts seem to have decided that it applies to almost any level of taxation.)

Keynesian theory says that in economic booms, you should reduce the outstanding debt, and in bad times, government should be ready to put money into the economy to jump-start it. The breakdown in the Keynesian consensus has been accompanied by a breakdown in the consensus that we should pay down the debt in good economic times.

Of course, partisan politics plays a part in all this, as we discussed in this post. Republicans don't mind increasing the debt when a Republican is in the White House, as we discussed here. In fact, the Republican consensus in favor of George W. Bush's stimulus package in 2008 would appear to show that they do, in fact, believe government action can jump-start the economy, and the Republican consensus against the Obama stimulus might actually be because they thought it might work, and help him get re-elected. Such strategic thinking might also be why Republicans were eager to force President Bill Clinton to cut the deficit, and voted repeatedly for tax and spending legislation during the second Bush administration that sent the deficit skyrocketing.

I think the problem here is that the Keynesian consensus has not really been replaced by either a new consensus or by two competing consensus (consensi?) Many of those determining our public policy have abandoned any real model of how the economy works, and now simply look for justifications for policies they want anyway.

For example, when the economy was booming and the budget was in surplus as President George W. Bush entered office, his solution to this policy challenge was to lower taxes. When the economy was hemorrhaging jobs and the budget was hemorrhaging red ink, his solution was a tax giveaway. Opposite conditions demanded the same response in his view, because any problem the country faced was an opportunity to pursue his political agenda.

This was the response of a man for whom economic analysis had no meaning; only political agendas had meaning.

On the Democrats' side, there is what might be called a weak Keynesian consensus. President Barak Obama, for example, seems to seek a middle ground between his own followers and the Republicans, a ground which arguably does not exist.

In any society, you must have elites who are expert on various topics, and can be counted on for sage words when advice is needed. We lack a consensus about who those experts are on any number of topics, in part because of a deliberate policy of agnotology, in part because dividing the nation was a deliberate strategy pursued by one of our political parties since the 1960s, a process very well described by George Packer's May, 2008 article on the subject in the New Yorker, which I keep finding myself urging people to read.

Nixon's Southern strategy depended on harnessing the resentment of Southern whites. Pat Buchanan wrote a 1971 memo to Nixon that encapsulated that strategy (which had been successful in the 1968 campaign) as using the resentments of Southern and working-class whites to “cut the Democratic Party and country in half; my view is that we would have far the larger half.”

Consensus and trust in elites are things more easily destroyed than restored, and thus far the electoral process is providing few incentives for our politicians to work this out.

Consider this, from Felix Salmon's financial blog:

"The base-case scenario is, still, that the debt ceiling will be raised, somehow. But already an enormous amount of damage has been done: the US Congress has demonstrated clearly that it can’t be trusted to govern the country in a responsible manner. And the tail-risk implications for markets are huge. Think of the speed with which the Egyptian government collapsed earlier this year, or the incredible downward velocity of News Corporation right now. When you build up large stocks of mistrust and ill will, nothing can happen for a very long time. But when something does happen, it’s much quicker and much worse than anybody could have anticipated. The markets might not be punishing the US government at the moment. But the mistrust and ill will is there, believe me. And when it appears, it will appear with a vengeance."

A legislature that "can’t be trusted to govern the country in a responsible manner" sounds more like the Italian government than the Japanese one. And that is an economic problem only because it is a political one.

Comments

Post a Comment